Medical stuff is not always polite.

We are taught as children not to put anything (at all!) up our noses, but many of us are now

learning how to do our own nasal swab for coronavirus testing.

Flushing toilets mean the waste our bodies produce can be politely disposed of. But what

our body produces can provide important information to our medical advisors.

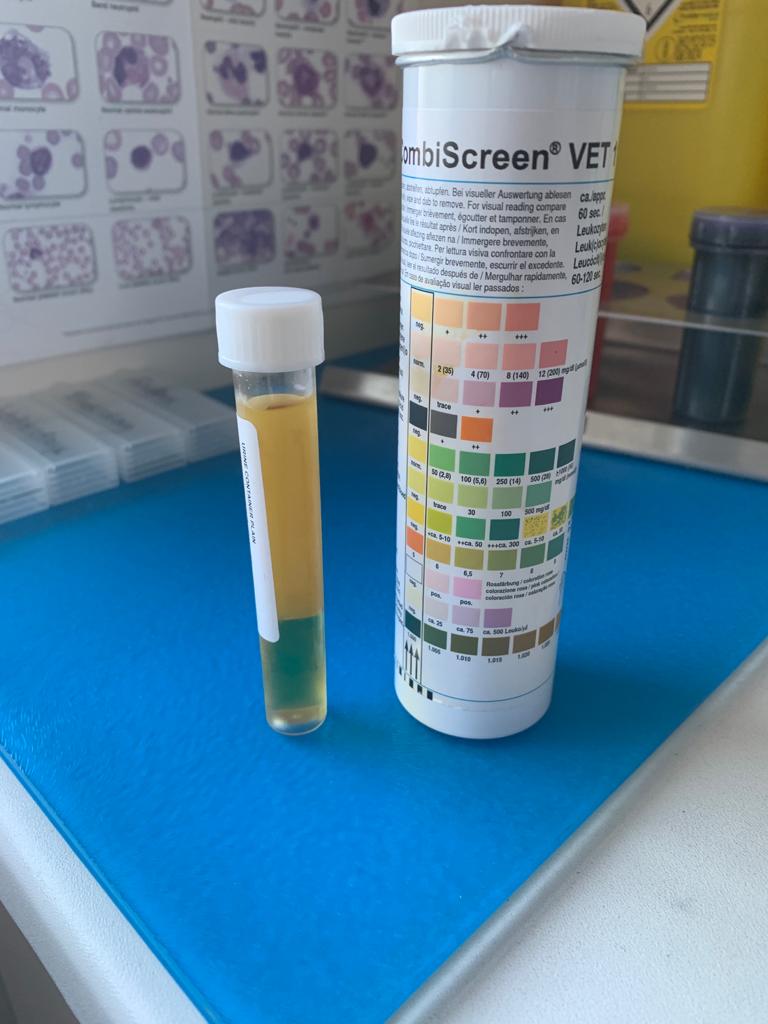

Urine samples can be invaluable to a vet.

They are also cheap to analyse, and results can be available within minutes.

In the last ten years or so, I would say that vets have become more and more likely to

request a urine sample from a patient.

We use them to check for diabetes mellitus, for cystitis, for the health of the kidneys, the

prostate and the bladder, and to give an indication of the kidney function. Urine samples

have become indispensable to monitor patients on long term non steroidal anti-inflammatory

medications (NSAIDs). We process many urine samples a day.

But sometimes getting the sample from a cat is interesting.

We have what we call ‘trick litter’, which can fool some cats into using the litter tray. But trick

litter does not absorb, so the sample is easy to pour out of the tray once provided, and the

cat just has to clean her paws afterwards.

But some cats have no intention of using a litter tray and will hold on for a day or more,

rather than not get the privacy they feel they deserve.

This is where cystocentesis is so helpful.

As long as a cat’s bladder is about the size of a satsuma or larger, I can use a needle to

draw off the sample of urine I need, straight through the belly muscles. Extraordinarily, the

vast majority of pets allow this without complaint. Even cleverer, just as the small hole I

make in a blood vessel to get a blood sample closes with the natural elasticity of the vein, so

does the little hole into the bladder.

Safely performing a cystocentesis allows me to help so many more patients.